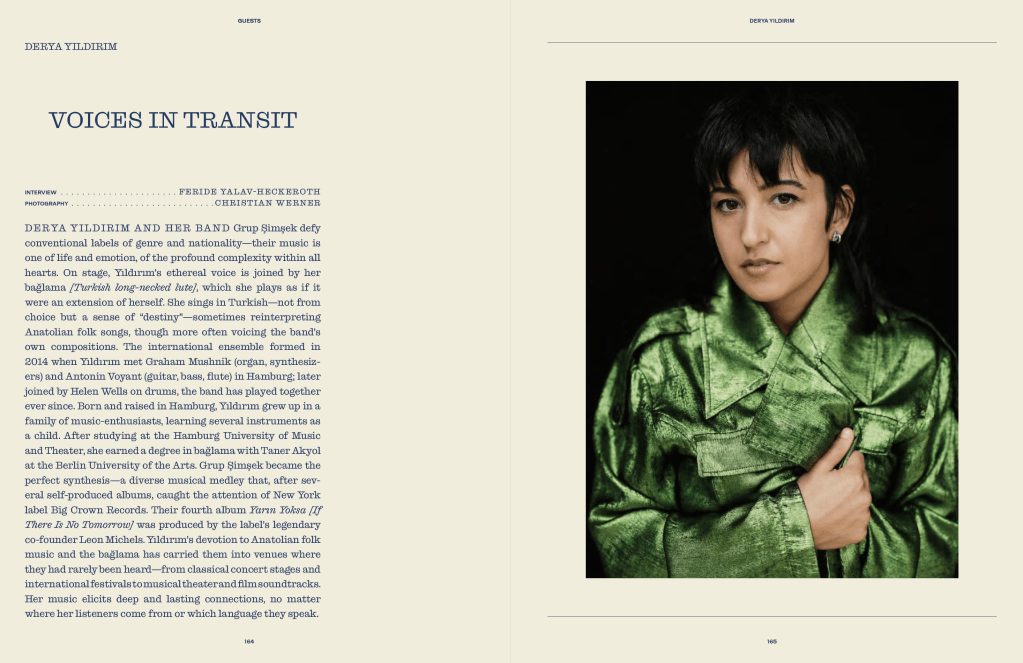

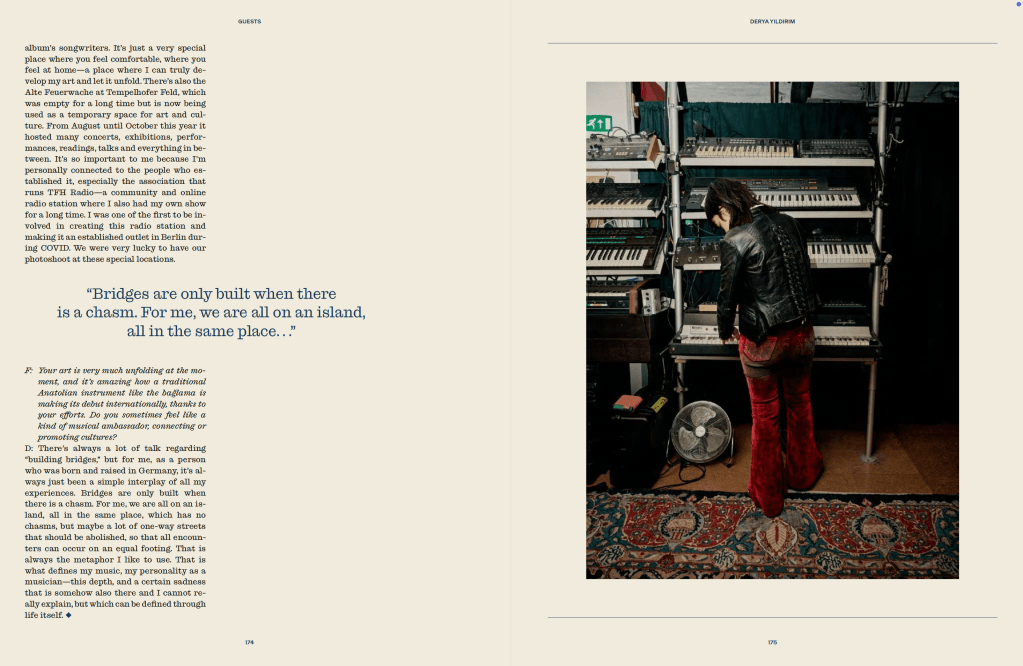

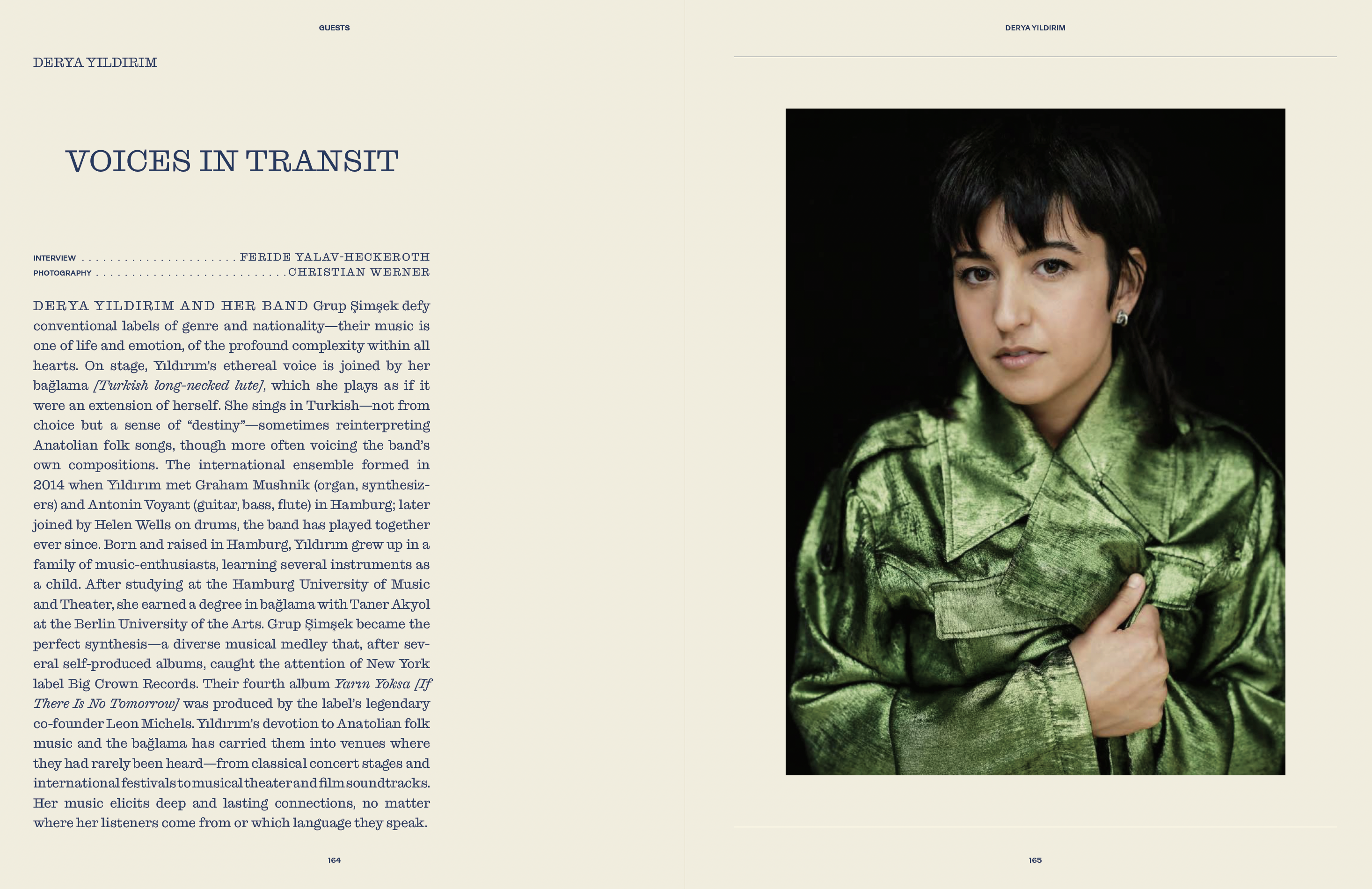

Derya Yıldırım and her band Grup Şimşek defy conventional labels of genre and nationality, for theirs is a music of life and emotion—of the profound complexity within all our hearts. On stage, Yıldırım’s ethereal voice is accompanied by her bağlama [Turkish long-necked lute] which she plays as if it were an extension of her body. She sings in Turkish—not out of volition but a sense of “destiny”—sometimes reinterpreting Anatolian folk songs, though more often giving voice to the band’s own compositions. The international ensemble formed in 2014 when Yıldırım met Graham Mushnik (organ, synthesizers) and Antonin Voyant (guitar, bass, flute) in Hamburg. Later joined by Helen Wells on drums, the band has been playing together ever since.

Born and raised in the North-German city of Hamburg, Yıldırım grew up in a family of music-enthusiasts, learning to play several instruments as a child. After studying at the Hamburg University of Music and Theater, she pursued a degree in bağlama with Taner Akyol at the Berlin University of the Arts. The formation of Grup Şimşek became the perfect synthesis—a diverse musical medley which, after several self-produced albums, caught the attention of the New York label Big Crown Records. The band’s fourth album Yarın Yoksa [If There is No Tomorrow] was produced by the record’s legendary co-founder Leon Michels.

As a solo artist, Yıldırım’s devotion to Anatolian folk music and the bağlama, especially in new contexts, has allowed her to carry them into venues where they had rarely been represented previously. From classical concert stages and international festivals to musical theater and film soundtracks, Yıldırım’s music has the capacity to elicit deep and lasting connections, no matter where her audience members hail from or which language they speak…

The Travel Almanac, TTA27 The Advent