Turkey’s wine scene is at the cusp of change–with a movement to revive indigenous grapes growing indefatigably–making it one of the world’s most exciting new countries for viticulture. It’s also a country of contradictions with the world’s fifth largest vineyard area, but only 3% of the annual grape harvest used for winemaking. A country where a 2013 legislation banned any promotion of alcohol, but which managed to snag more than 1,000 medals and commendations at the Decanter World Wine Awards over the years since it started in 2004.

To understand Turkey’s unique viticulture, it’s essential to glance at its past. With southeastern Anatolia believed to be the location where the grapevine was first domesticated around 9,500-5,000 BC, viticulture in the seven geographical regions that now compose modern Turkey existed continually throughout the centuries and although alcohol was prohibited during the Ottoman era, non-Muslim communities were allowed to manufacture and trade it.

The breaking point occurred in 1923, when, during the aftermath of WWI and the Turkish War of Independence, Armenian and Greek communities (the country’s main wine producers) were forced to migrate. Vineyards and wineries were abandoned and efforts to revive them during the newly formed secular Turkish Republic eventually led to a state-run monopolistic market for much of the 20th century. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Turkey’s first boutique vineyards emerged, planting international grape varieties often under the guidance of foreign consultants.

“In the early ‘90s Doluca, Turkey’s oldest wine producer, began to produce fine wines from international grapes. Around the same time, Kavaklıdere, another long-established producer, started to produce local Öküzgözü, Boğazkere and Kalecik Karası wines. We can say that these two events were milestones in Turkey’s modern winemaking story,” says Levon Bağış, one of Turkey’s foremost wine experts.

Bağış co-founded Yaban Kolektif, a nomadic viticulture project that endeavours to return endangered grape varieties into commercial activity and save them from extinction. “Nowadays, small and large producers are focusing on native varieties – this and the natural wine movement have brought real excitement to Turkish winemaking.”

According to the Tekirdağ Viticulture Research Institute, Turkey has 1,435 grape varieties, most of which are grown on old vines. However, for a mostly Muslim country, where the annual average wine consumption is less than one liter per capita, grapes don’t always translate into wine. A tiny percentage of the annual grape harvest is used for wine, while the rest is either consumed fresh, made into molasses, raisins, vinegar or rakı (Turkey’s popular aniseed flavored spirit).

“I say thank you to the molasses and the raisins for protecting and maintaining these indigenous grapes. You can take a shoot from these historic vines and plant them somewhere else and they will flourish,” says Sabiha Apaydın Gönenli, wine director of Istanbul’s famous Mikla restaurant, co-founder of Heritage Vines of Turkey and founder and organiser of the annual wine conference Root Origin Soil (Kök Köken Toprak).

“When we began our research with Heritage Vines of Turkey, there were about 20 local grape varieties used commercially – we have managed to increase this number to 65,” says Apaydın. “What we typically find are not vineyards, but gardens, 2-3 acres in size, but all of them with historic gobelet vines.”

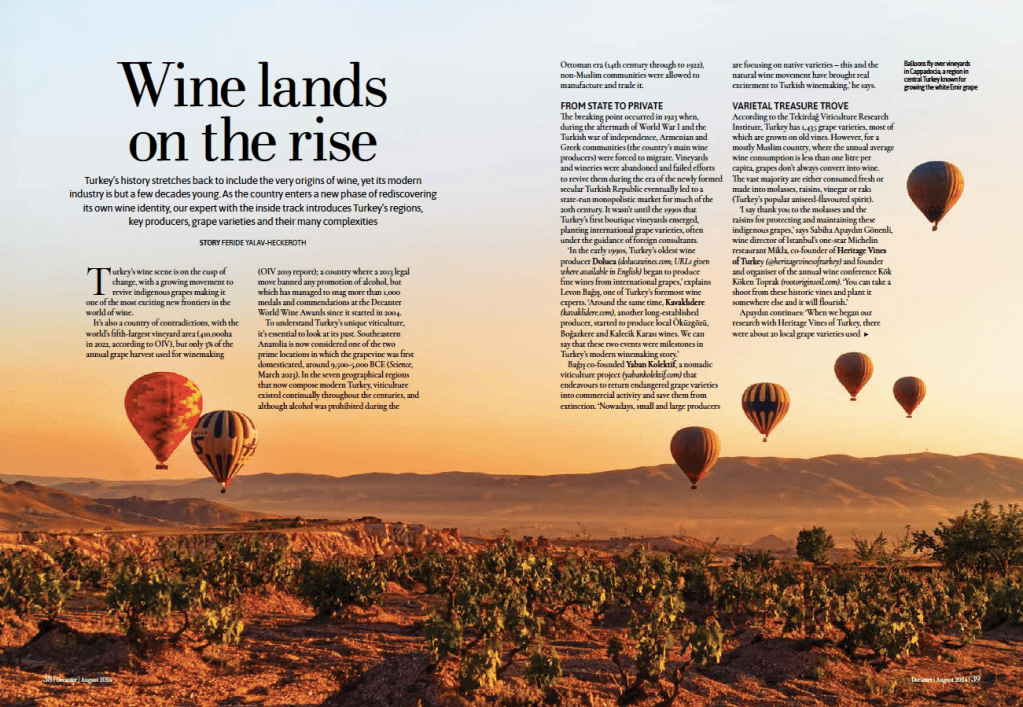

Currently, Turkey has around 185 wine producers and its most important viticultural regions include Cappadocia, known for its Emir grape; Tokat, where Narince grapes are grown; the Elazığ and Diyarbakır provinces, where Öküzgözü and Boğazkere grapes are grown; and Ankara, where the Kalecik Karası grape reigns. Urla, a district in Izmir along the Aegean coast, has recently been in the limelight with its vineyard route connecting nine producers. The Marmara region, as well as Tekirdağ, Çanakkale and Kırklareli are also important areas for the production of both international and local grapes.

However, newly emerging regions like the vineyards at an altitude of 1,800 meters on the edge of Lake Van in Eastern Anatolia, are just beginning to be discovered as demand and curiosity for native grapes grows. Due in part to thousands of young people trained by The Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET) and the use of social media to promote Turkish wine, a new community focused on dynamic, local and quality-oriented wine production has emerged. One of the Heritage Vines of Turkey projects focused on the revival of the Mut and Silifke districts, for example, where ancient vineyards thrive in challenging and non-irrigable sloped terrains with Aküzüm (white), Patkara (red) and Gök (white)harvested by local villagers. The local vineyard Tasheli Wines has been working with these grapes for years and is making a name for itself. Established vineyards such as Doluca, Chamlija, Kayra, Urla Wines, Suvla and 7Bilgeler have also supported the research by producing wines from these newly discovered local grapes.

“Even though Turkey is not widely recognised in the wine world, as two oenologists, we were aware of the value of these lands. It’s a vast country, encompassing a wide range of geographical features, and still boasts a rich variety of grapes. What led us here was our belief in the potential of these soils and our eagerness to bring it to light,” says Akinci, who met her spouse and business partner Hernandez while studying oenology in Bordeaux. Their estate Heraki, founded in 2019, produces monovarietal wines from 35- to 80-year-old dry-farmed bush vines of Sultaniye, Çal Karası and Boğazkere grapes from Çal, Denizli, as well as Gök, Patkara and Karasakız grapes from the Bayramiç region in the Çanakkale province, with the support of the Heritage Vines of Turkey project.

With Udo Hirsch and Hacer Özkaya – the founders of Gelveri in Cappadocia and the first to produce natural wines from indigenous grapes fermented and aged in Roman amphoras – as her mentors, Gizem Billur Duyar created Kerasus Wines in 2018 to revive the indigenous grapes of the Black Sea region. Working with married vines (vines that cling to trees for support), Duyar works with villagers to harvest their garden-grown grapes, using a specially made amphora designed by a master artisan in Cappadocia.

“Married vine is an ancient viticulture technique and aims to explain the relationship between vines and the trees they embrace. Even though the vine belongs to the ivy family, it does not harm the tree. They live a life together,” says Duyar. “Married vines are abundant in the Black Sea region.”

Another vineyard focused mainly on the production of indigenous grapes is Paşaeli, founded by Seyit Karagözoğlu in 2000. Focusing on grape varieties close to Paşaeli’s winery in Kemalpaşa, İzmir, Karagözoğlu discovered the thin-skinned red Karasakız, turning it into an elegant vintage by 2009, convincing domestic consumers, who were used to big and bold Bordeaux wines, that a light-coloured red was just as enjoyable on the palate.

Part of the newly formed Çal Bağ Yolu (Çal Wine Route) with a minimalist concrete facility that rises above the grapevines, Kuzubağ focuses on the revival of the indigenous Çal Karası and Sultaniye grapes, as well as, more recently, the Acıkara grape from Antalya. “When Çal Karası received its first international gold medal, the locals celebrated with us,” says Aslı Kuzu, one of the country’s youngest female winemakers. “We think that anything is possible if we believe in our own grapes and introduce them correctly.”

In the well-heeled Istanbul neighborhood of Nişantaşı, Foxy – one of the city’s only wine bars focusing on local wines and co-opened by none other than Levon Bağış – does its best to educate wine lovers, feeding their curiosity for the many native grapes of this vast country. “I think no other future is possible other than Turkish wine producers focusing primarily on native grape varieties. We may need a few lifetimes to discover all the grapes grown in Turkey and to reveal their potential. But it’s worth it,” says Bağış.

Decanter Magazine, August 2024 (print and online)